So the other day I was wasting time looking at Facebook profiles (I’m giving that up, by the way) and I saw a discussion about whether workers were “free” in a free market.

So the other day I was wasting time looking at Facebook profiles (I’m giving that up, by the way) and I saw a discussion about whether workers were “free” in a free market.

The answer was no. Workers are not free because they cannot get paid as much as they want.

This is a delusional way to think about the question. We all wish we could get paid more than we are. That is human nature.

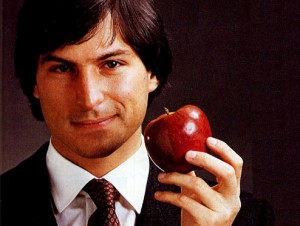

Look at it this way, What company would stay in business if it announced it was cutting wages in half tomorrow?

Both owners and workers have to face economic realities. The owners cannot pay anyone more than they can afford. Otherwise they go out of business. They cannot afford to pay workers less than those workers can get elsewhere, or else they go out of business.

Wages, like all prices, fluctuate. The idea that wages as measured in currency should always go up is a fantasy.

And even talking about wages that way distracts from an important way that workers, as consumers, are constantly giving themselves raises. In fact, it looks like a new clothing allowance is on the horizon:

Penney’s slashing prices on all merchandise – USATODAY.com.

Penney is permanently marking down all of its merchandise by at least 40% so shoppers will no longer have to wait for a sale to get the lowest prices in its stores.

So, what used to cost a hundred dollars to buy, normally, may soon only cost sixty dollars. I suspect other companies will be “forced” (!) to follow Penney’s lead. That is a raise. For everyone. And it is the result of the real and true “collective bargaining”–the market.

But then we get this wisdom from Robert Reich:

Modern technologies allow us to shop in real time, often worldwide, for the lowest prices, highest quality, and best returns. Through the internet we can now get relevant information instantaneously, compare deals and move our money at the speed of electronic impulses. Consumers and investors have never been so empowered.

Yet these great deals come at the expense of our jobs and wages, and widening inequality. The goods we want or the returns we seek can often be produced more efficiently elsewhere by companies offering lower pay and fewer benefits. They come at the expense of main streets, the hubs of our communities.

First, of all, there is a lot more in Reich’s column about pollution and the environment. He makes assertions without evidence so I don’t feel the need to respond. I just bring it up to point out that it is there too, and it is a different argument.

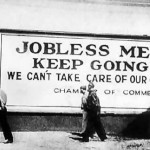

Above, his argument is that buying cheaper products is an economic problem. It is absolutely true that a “main street” that has been dependent on an inefficient factory that employed most of the people is going to have to close. It should. The people should find work elsewhere. Chaining consumers to such people is slavery.

In what world do factories never close? In what world does the way things are made never change, never get improved, never get supplied by a new producer?

A lifeless world. A dead planet.

In this living world we are all, everyone of us, are trying to produce and consume as best we can. In this living world there is constant change and we have to learn and help and adapt and enjoy.

The idea that this process–the mere living of a society–must result in widening inequality is theoretically illogical and historically false. We know why inequality is beginning to widen: because of the omnivorous, ever-hungry state. It has corrupted currencies all over the world in order to fund a ruling regime, a finance-political complex. In this environment, we have been slowly losing ground for decades as saving has been discouraged and debt has been encouraged. Reich pining for higher prices is just another attempt to keep the status quo going.

The efficiency of trade is impossible if the medium of exchange can be tampered with by politicians/state-bankers.

Look at what Reich is actually saying. Information should be hampered. Transportation should be slowed. Prices should rise. Ignorance, geographical barriers, and higher prices are what we should all want. We would all be better off.

In a way I think Reich is telling us the truth. He is telling us what the political establishment can and will “provide” for us–and is trying to make a case that it is a social good.

Which is preferable for man and for society, abundance or scarcity?

“What!” people may exclaim. “How can there be any question about it? Has anyone ever suggested, or is it possible to maintain, that scarcity is the basis of man’s well-being?”

Yes, this has been suggested; yes, this has been maintained and is maintained every day, and I do not hesitate to say that the theory of scarcity is by far the most popular of all theories. It is the burden of conversations, newspaper articles, books, and political speeches; and, strange as it may seem, it is certain that political economy will not have a completed its task and performed its practical function until it has popularized and established as indisputable this very simple proposition: “Wealth consists in an abundance of commodities.”

Do we not hear it said every day: “Foreigners are going to flood us with their products”? Thus, people fear abundance.

Has not M. de Saint-Cricq said: “There is overproduction”? Thus, he was afraid of abundance.

Do not the workers wreck machines? Thus, they are afraid of overproduction, or—in other words—of abundance.

Has not M. Bugeaud uttered these words: “Let bread be dear, and the farmer will be rich”? Now, bread can be dear only because it is scarce. Thus, M. Bugeaud was extolling scarcity.

Has not M. d’Argout based his argument against the sugar industry on its very productivity? Has he not said again and again: “The sugar beet has no future, and its cultivation cannot be extended, because just a few hectares of sugar beets in each department would be enough to supply all the consumers in France”? Thus, as he sees things, good consists in barrenness and scarcity; and evil, in fertility and abundance.

Do not La Presse, Le Commerce, and the majority of the daily newspapers publish one or more articles every morning to prove to the Chambers and to the government that it is sound policy to legislate higher prices for everything through manipulation of the tariff? Do not the Chambers and the government every day comply with this injunction from the press? But tariffs raise the prices of things only because they reduce their supply in the market! Thus, the newspapers, the Chambers, and the government put the theory of scarcity into practice, and I was right to say that this theory is by far the most popular of all theories.

Contra Reich, I assert that the economy will, if allowed to do so by the politico-finance complex, provide more for all if prices are allowed to fall (and rise) under market forces. Since Reich provides no evidence or arguments that free exchange causes poverty and widening inequality, I won’t burden myself with doing more than stating the obvious.